Auschwitz – A Chronicle of Tragedy, Memory, and Hope

At least sixty kilometres southwest of Cracow lie Auschwitz (Oświęcim in Polish) and Birkenau (Brzezinka) — names forever etched into history as symbols of unprecedented human suffering and systematic mass murder. At the same time, they stand as a stark and enduring warning of the consequences of hatred, indifference, and dehumanisation.

From a Political Prison to the Epicentre of the Holocaust

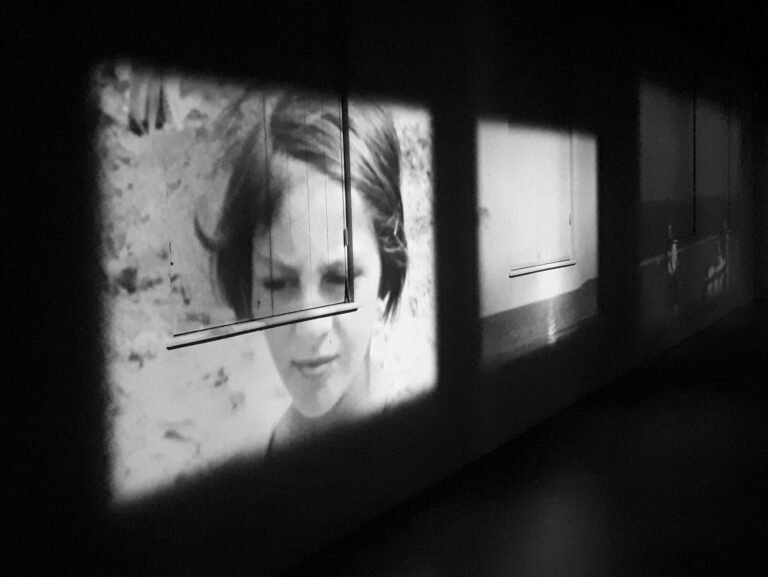

Auschwitz was established by Nazi Germany in June 1940, in the early phase of the Second World War. Initially, it functioned primarily as a concentration camp for Polish political prisoners: members of the resistance, representatives of the intelligentsia, and civilians arrested during random round-ups aimed at terrorising the population and suppressing Polish national identity. Prisoners were subjected to brutal forced labour, starvation, severe punishment, and pseudo-medical experiments. In the spring of 1942, women were imprisoned in Auschwitz; later that same year, children were deported there as well.

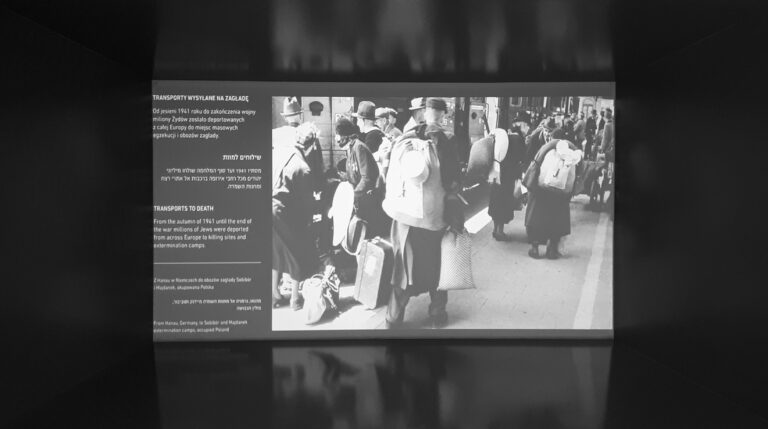

As the war progressed and Nazi racial policy escalated, Auschwitz underwent a radical and horrific transformation. Following the Wannsee Conference in January 1942 and the decision to implement the so-called “Final Solution of the Jewish Question,” Auschwitz became a central site of industrialised murder. The construction of Auschwitz II–Birkenau, which began in the autumn of 1941, marked a decisive turning point. Originally intended as a camp for Soviet prisoners of war, Birkenau was instead equipped with gas chambers and crematoria designed for the mass exterminination of European Jews.

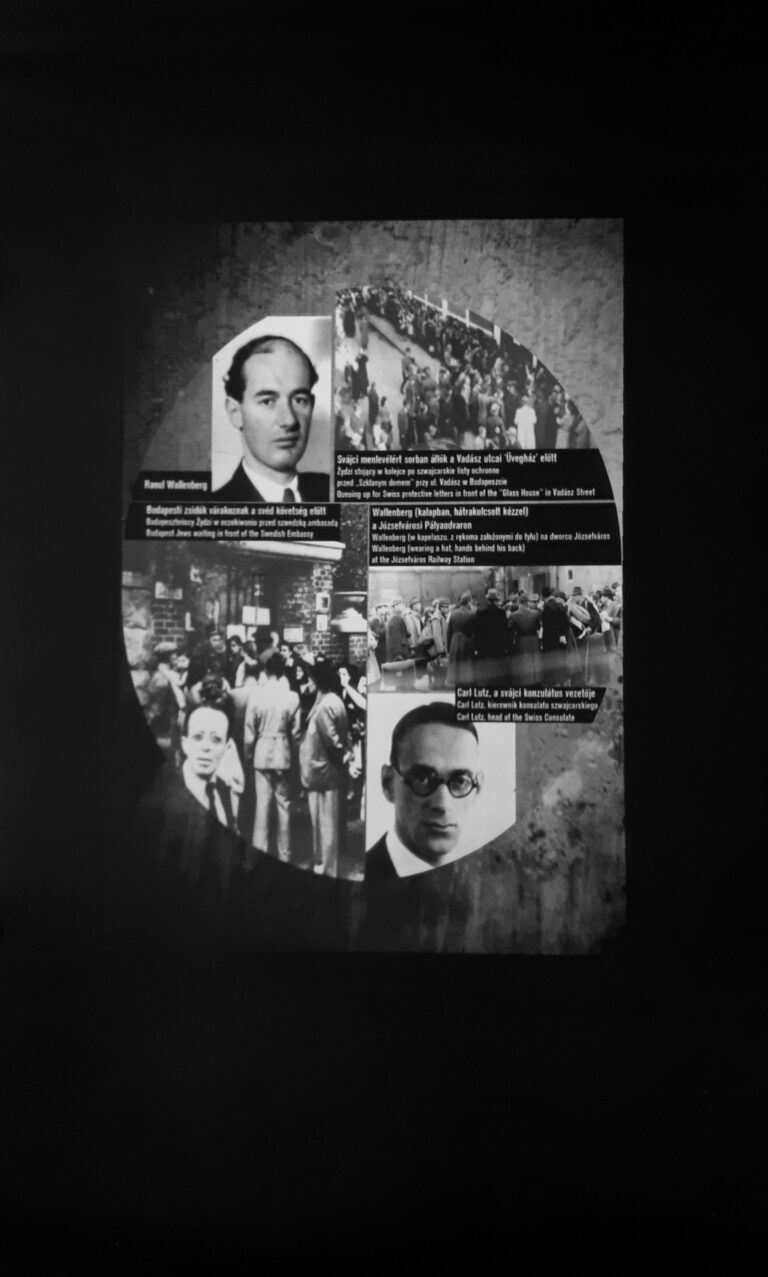

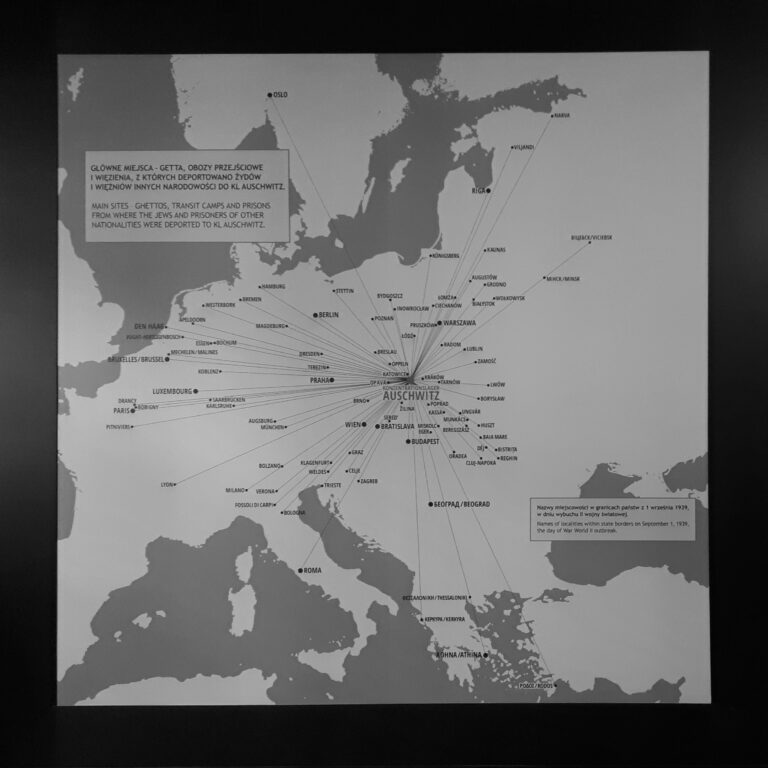

From the spring of 1942 onward, deportations intensified. Jews from many parts of Europe were transported to Auschwitz in vast numbers — from Poland, Hungary, France, the Netherlands, the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, Italy, Belgium, Yugoslavia, Slovakia, Norway, and other countries. Upon arrival, men, women, and children were subjected to selection. The majority — approximately 75–80 percent of each transport, including most children, women with young children, the elderly, the sick, and people with disabilities — were deemed unfit for labour and sent directly to the gas chambers.

Numbers That Defy Comprehension

At least 1.3 million people were deported to Auschwitz during its operation. Of these, an estimated 1.1 million were murdered. The vast majority of victims were Jews, though Poles, Roma, Soviet prisoners of war, and others were also killed.

Providing precise statistical breakdowns is difficult, due to incomplete records. However, widely accepted estimates indicate that among the Jewish victims were approximately:

- 430,000 Jews from Hungary

- 300,000 Jews from Poland

- 69,000 Jews from France

- 60,000 Jews from the Netherlands

- 55,000 Jews from Greece

- 46,000 Jews from the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia

- 27,000 Jews from Slovakia

- 25,000 Jews from Belgium

- 10,000 Jews from Yugoslavia

- 7,500 Jews from Italy

- 690 Jews from Norway

These figures are not merely statistics — they represent individual lives, families, and entire communities erased.

The Camp Complex and Liberation

Over time, the Auschwitz complex expanded to include more than forty subcamps spread across southern Poland and neighbouring regions. The core of the system consisted of three main camps:

- Auschwitz I: the main camp

- Auschwitz II–Birkenau: the extermination site

- Auschwitz III–Monowitz

Major companies, including IG Farben, exploited prisoners as slave labourers in factories and mines, demonstrating the close entanglement of industry and genocide. Auschwitz thus functioned simultaneously as a site of imprisonment, forced labour, and mass murder — a central mechanism of the Nazi system.

In the spring of 1944, Auschwitz witnessed some of the final and most dramatic events of its existence. Deportations continued, particularly of Hungarian Jews. In October 1944, members of the Sonderkommando — Jewish prisoners forced to work in the crematoria — staged an armed uprising, destroying one of the gas chambers in a desperate act of resistance. Though the revolt was crushed, it remains a powerful testament to human courage in the face of annihilation.

As Soviet forces advanced, the Nazis began dismantling the camp and evacuating prisoners. Tens of thousands were forced onto death marches toward the west, during which many perished from exhaustion, cold, and execution.

On 27 January 1945, Auschwitz was liberated by the Soviet Red Army. What the soldiers discovered revealed the full scale of the crimes committed there. This date is now observed internationally as Holocaust Remembrance Day.

Auschwitz After the War — Meaning for the Future

In 1947, the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum was established on the site, largely through the efforts of former prisoners. Today, Auschwitz serves as a memorial and museum, dedicated to education, remembrance, and warning future generations.

Auschwitz stands as testimony to both the depths of human cruelty and the resilience of the human spirit. Remembering at least 1.1 million people murdered here is not only an act of historical memory — it is a moral responsibility.

The legacy of Auschwitz extends beyond history into the ethical fabric of the present and the future. It reminds us of the inherent dignity and value of every human life. It calls on us to confront prejudice, hatred, and indifference wherever they appear.

Auschwitz is not only a place of death. It is also a place of warning — and, ultimately, a call to action. To remember is not enough. We are compelled to build a world in which such crimes can never occur again.